Follow Danielle on Instagram!

Follow Danielle on Twitter!

|

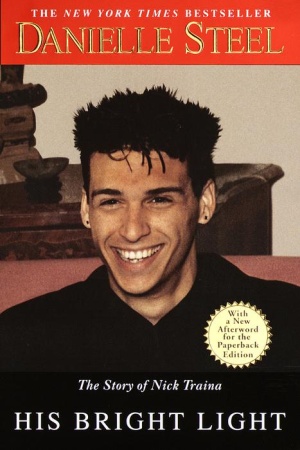

Prologue This will not be an easy book to write, but there is much to say, in my own words, and my son’s. And as hard as it may be to write, it’s worth doing, if it helps someone. It is hard to encapsulate a being, a very special being, a soul, a smile, a boy, a huge talent, an enormous heart, a child, a man, in however many pages. Yet I must try, for him, for myself, for you. And I hope that as I do, you will come to understand who he was, and what he meant to all those who knew him. This is the story of an extraordinary boy, with a brilliant mind, a heart of gold, and a tortured soul. It is the story of an illness, a fight to live, and a race against death. It is early days for me yet, as I write this. He has been gone a short time. My heart still aches. The days seem endless. I still cry at the sound of his name. I wander into his room and can still smell his familiar smell. His words still echo in my ears. He was alive only days, weeks ago . . . so little time, and yet he is gone. It is still impossible to absorb or understand. Harder still to accept. I look at his photographs, and cannot imagine that all that life and love and energy has vanished. That funny, handsome face, that brilliant smile, the heart I knew better than my own, the best friend he became to me, can they truly be gone? Do they live only in memory? Even now, it remains beyond my comprehension, and is sometimes beyond bearing. How did it all happen? How did we lose him? How could we have tried so hard, and cared so much, and loved him so enormously, and still have lost him? If love alone could have kept him alive, he would have lived to be three hundred years old. But sometimes, even loving with all your heart and soul and all your mind and will just doesn’t do it. Sadly, it didn’t do it for Nick. If I had three wishes, one would be that he had never suffered from mental illness, the other would be of course that he were alive today, but the third would be that someone had warned me, at some point, that his illness–manic depression–could kill him. Perhaps they did. Perhaps they told me in some subtle way. Maybe the inference was there, and I didn’t want to hear it. But I listened carefully to everything that was said to me over the years, I examined every nuance, and to the best of my knowledge and abilities, heeded every warning. My recollection is that no one told me. Certainly not clearly. And it was a piece of information that I desperately needed. I’m not sure we would have done things any differently, but at least I would have known, been warned, of what the worst case could be. His illness killed him as surely as if it had been a cancer. I wish I had known that, that I had been warned how great the risk was. Perhaps then I would have been better prepared for what came later. I’m not sure that in the minds of the public it is clear that bipolar disease, manic depression as it’s more commonly called, is potentially fatal. Not always certainly, but in far too many cases. Suicide and accidents appear to be the greatest cause of death for manic-depressives. Neither are uncommon. If I had been told that he had cancer of a major organ, I would have known with certainty how great the risk was. I might have understood how short his life could be, how tragic the implication. I’m sure I would have fought just as hard, just as long, just as ingeniously, but I would have been better prepared for what came later. The defeat might not have been quite as startling or as stunning, though it would surely have been just as devastating. The purpose of this book is to pay tribute to him, and to what he accomplished in his short life. Nick was an extraordinary human being, with joy and wisdom, and remarkably profound and astute perceptions about himself and others. He faced life with courage and panache and passion and humor. He did everything “more” and better and harder. He loved harder and more, he laughed a lot, and made us laugh, and cry, and try so hard to save him. No one who met him was left unimpressed or unaffected. You couldn’t meet him and not give a damn. He made you care and feel and want to be as big as he was. He was very big. The biggest. I have written this book to honor and remember him. But there is yet another purpose in writing this book. I want to share the story, and the pain, the courage, the love, and what I learned in living through it. I want Nick’s life to be not only a tender memory for us, but a gift to others. There is much to learn here, not only about one life, but about a disease that afflicts between two and three million Americans, one third of whom, it is believed, die from it, possibly as many as two thirds. That is a terrifying statistic. The statistics are somewhat “soft” on the issue of fatalities, because often death is attributed to other things, for instance “accidental overdose” rather than suicide, which is determined by the actual amount of fatal substances ingested, rather than by clear motive. It is debatable as to whether or not those who have died could have been saved, or if those who will die can be. But what of those who will live, and have lived, and are still living? How do we help them? What can we do? Sadly, no one, and certainly not I, has the magic answers to solve the problem. There are different options, different solutions, a variety of ways of coping. But first, you have to see the problem. You have to understand what you’re dealing with, to accept that what you’re dealing with is the equivalent of not just a bellyache, but liver cancer. You have to know that what you’re facing is serious, important, dangerous, and potentially fatal. Somewhere out there, in apartments, and homes, and hospitals, in ordinary jobs and lives, and not just psychiatric wards, are people coping with a terrible struggle within them. And alongside them are the people who know and love them. I would like to reach out here, and to offer hope and the realities we lived with. I want to make a difference. My hope is that someone will be able to use what we learned, and save a life with it. Maybe you can make a difference, even if I couldn’t. If it is true that one third of manic-depressives die of this disease, and its related burdens, then two thirds will live. Two thirds can be helped, and can live a useful existence. And if possible, I would like Nick’s story, and Nick’s life, to help them, to serve them, perhaps to learn from our mistakes, and our victories. The greatest lessons I learned were of courage, and love, energy, ingenuity, and persistence. We never gave up, never turned away, never turned on him, never let him go, until he let us go, because he couldn’t fight the fight any longer. We not only gave him CPR when he attempted suicide, but we tried to keep his soul alive in every way we could, so that he could keep fighting the fight along with us. And the real victory for him, and for us, was that we gave him a quality of life he might otherwise never have had. He was able to pursue a career he loved, in music. He saw victories that few people do, at twice his age, or who live a great deal longer. He knew the joy and excitement of success, and also knew better than most the price he paid for it. He had friends, a life, a family, a career, he had fun and happiness and sorrow. He moved through the last few years of his life with surprising grace, despite the handicaps he was born with. And we were incredibly proud of him, as a man, a musician, and a human being. He was a talented, brilliant young man with a disease. But the disease did not stop him from being who he was, or us from loving him as he was. In retrospect, I think it was one of the best gifts we gave him. Acceptance of who he was, and unconditional love. In our eyes at least, his illness was only one facet of him, not the whole of him. There is no denying that it is a hard, hard road, loving someone with bipolar disease. There are times when you want to scream, days when you think you can’t do it anymore, weeks when you know you haven’t made a difference and only wish you could, moments when you want to turn your back on it. It is their problem, not yours, and yet it becomes yours if you love the person suffering from it. You have no choice. You must stand by them. You are trapped, as surely as the patient is. And you will hate that trap at times, hate what it does to your life, your days, your own sanity. But hate it or not, you are there, and whatever it takes, you have to make the best of it. I can only tell you what we did, what we tried, what worked, and what failed. You can learn from what we tried to accomplish, and develop better avenues that work for you. We tried a lot of things, and flew by the seat of our pants some of the time. There are no rule books, no manuals, no instruction sheets, no norms. You just have to feel your way along in the dark and do the best you can. You can’t do more than that. And if you’re very lucky, what you’re doing works. If you’re not, it won’t, and then you try something else. You try anything and everything you can until the very end, and then all you have is knowing how hard you tried. Nick knew. He knew how hard we tried for him, and he tried too. We respected each other so much for it. We loved each other incredibly because we had been through so much together, and we cared so much. He and I were very much alike actually, more than we realized for many years. He said it in the end. He made me laugh. He made me smile. He was not only my son, but my best friend. And I am doing this for him, to honor him, and to help those who need to know what we learned, what we did, what we should have done, and shouldn’t have done. And if it helps someone then it is worth reliving it all, and sharing his joys and his agonies with you. I am not doing it to expose him, or myself, but to help you. Would I do it all again? Yes. In a minute. I wouldn’t give away these nineteen years for anything in the world. I wouldn’t give up the pain or the torment or the sheer frustration, or the occasional misery of it, because there was so much joy and happiness that went with it. There was nothing better in life than knowing that things were going well for him. I would not have missed a single instant with him. He taught me more about love and joy and courage and the love of life and wonderful outrageousness than anything or anyone else in my life ever will. He gave me the gifts of love and compassion and understanding and acceptance and tolerance and patience, wrapped in laughter, straight from his heart. And now I share these gifts with you. Love is meant to be shared, and pain is meant to be soothed. If I can share your pain, and soothe it with the love Nick shared with all of us, then his life will be yet one more gift, not only to me and his family this time, but to you. It was Nick who made it all worthwhile, and worth fighting for. He did it for us, and for himself, and we for him. It was a dance of love from beginning to end. His was a life worth living, whatever the handicaps and challenges. I think he’d agree with that. And I have no doubt of it. I have no regrets, no matter how hard it was. I wouldn’t have given up one second with him. And what happened in the end was his destiny. As his song says, “Destiny . . . dance with me, my destiny.” And how sweet the music was. The sound of it will forever live on, just like Nick, and our love for him. He was a priceless gift. He taught me everything worth knowing about life and love. May God bless and keep him, and smile with him, until we meet again. And may God keep you safe on your journey. d.s. Excerpted from His Bright Light by Danielle Steel. Excerpted by permission of Delta, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Penguin Random House US | Random House US | Penguin Random House Canada